When choosing to remake a film, the greatest challenge often lies not in modernizing the narrative, but in artistically justifying the project’s very existence. Gustav Möller’s version of “The Guilty” (2018) had already established a firm foundation by exposing the emotional cracks within the structure of police authority. Three years later, Antoine Fuqua revisits the material, and it is precisely the raw maintenance of the human perspective that prevents his retelling from sinking into the tepid waters of redundancy.

Embracing the unspoken maxim that “when a formula works, it’s wise to alter little,” Fuqua crafts a restrained and conscious adaptation. Nic Pizzolatto’s script, though introducing subtle changes, dedicates itself to expanding the spotlight on the shadowy recesses of police psychology. The cold bureaucracy of institutional procedures — often hailed as a safeguard against human fallibility — is pushed to the background. In its place emerges the volatile collision between instinct and duty, where even the most rigorous training can be overwhelmed by the simple, conflicted nature of being human.

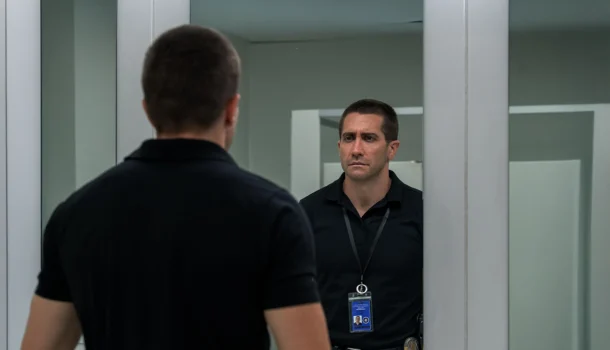

Jake Gyllenhaal inhabits Joe Baylor with a level of vulnerability that never veers into sentimental concession. Discreet elements, like the inhaler that punctuates the tension with banal presence, offer narrative breathing spaces without diluting the existential weight the film imposes. Baylor, manning the emergency calls, is a figure besieged by his own conscience, a man whose lapses and virtues intertwine into an inextricable knot. Every call received slices deeper into his emotional armor, exposing old wounds while new ones struggle to heal.

This dynamic reaches its apex in the contact with Emily, the panicked voice brought to life by Riley Keough. The decision to keep her offscreen is anything but gratuitous: by removing her physical presence, Fuqua and Pizzolatto force attention onto the non-verbal cues — the hesitations, tones, and fractures in speech. Keough builds an Emily brimming with nuance, as plausible as she is unsettling, transforming physical absence into absolute presence. Baylor, clinging to the protocol of closed-ended questions, fights against the current of his own instincts, but his impulsive nature sabotages him, dragging him into a spiral that mirrors both his compassion and his barely contained arrogance.

The plot makes no effort to disguise its intent: to quietly but firmly discuss the inevitable friction between police professionalism and the erosion of rationality under extreme pressure. Baylor, demoted and disgraced, becomes a shattered mirror of a system that fails both to restrain its own excesses and to protect its humanity. His downfall is not a mere moralistic punishment but an invitation to discomfort: how realistic is it to expect sterile behavior from those tasked with facing the abyss daily? At what point does a personal failure reveal itself as systemic?

Antoine Fuqua doesn’t simply revisit Alfred Hitchcock — he understands and updates him, fully aware that the most potent suspense is born of internal tension. Thus, “The Guilty” subtly echoes “Rear Window,” “Dial M for Murder,” and “Vertigo,” without ever seeming derivative. Fuqua guides Gyllenhaal into deepening Baylor’s psychological fragmentation, turning his quest for redemption into a mirage where each attempt to save another reflects a desperate yearning to save himself. The narrative, far from offering solutions, exposes the futility of emotional shortcuts in a landscape where redemption is rarely pure or linear.

Joe Baylor’s decline is woven without any glamorization of the anti-hero archetype. Instead, the film opts for starkness: downfall as the logical sequence of minor transgressions, failure as an inescapable trait of human nature. As Baylor sinks deeper into his own contradictions, he illuminates the fragile boundary between those who protect and those who, in the act of protecting, are corrupted by their own passions.

“The Guilty” never offers itself as a redemptive allegory. Its strength lies precisely in the discomfort it provokes, in the unease of watching a man who, despite his best intentions, stumbles over the very stones he himself has laid. There is no easy catharsis, no full reconciliation — only the bitter realization that heroism, in its most credible form, is woven with flaws, regrets, and, above all, desperate choices.

Film: The Guilty

Director: Antoine Fuqua

Year: 2021

Genre: Thriller

Rating: 9/10